Introduction

In this article, I will show that it is incorrect to assume that “observation” can be used to find out a person’s gender or sex.

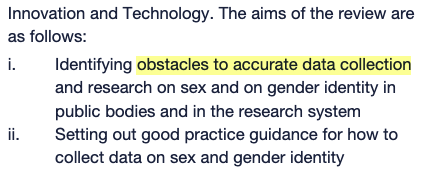

Surveys and other forms of data collection often use “observational coding”, meaning that the interviewer simply records what they assume the gender/sex of the person being interviewed to be. This approach is specifically endorsed by the trans-hostile Sullivan Review, which made a large number of sweeping and harmful recommendations to the UK government about data, statistics and research.

The European Social Survey (ESS), a large-scale survey of social attitudes run by multiple countries since 2001, has used “observational coding” throughout its history: a “gender” data item is used by interviewers to record each participant as either “male” or “female”.

However, in the most recent ESS round, an additional question on “non-binary gender” also captured the participants’ self-reported gender. This question allowed for a broader range of answers including “a man”, “a woman”, and “other”.

The parallel use of these two different “gender” items allows us to directly compare “observation” and “self-report” data about gender/sex; as we will see, the level of disagreement between them can only result from “observational coding” being unreliable.

This implies that Sullivan is wrong, and that “observational coding” should be discontinued entirely: using this approach may introduce serious inaccuracies in data, raising problems of data interpretation and potential legal issues.

I will also note problems with the ESS “non-binary gender” question, and discuss how to avoid those issues when designing survey questions to capture gender/sex inclusively.

Assumptions About “Observing” Sex

The practice of “gendering” a person based on a glance is so commonplace that it is generally unremarked and unconsidered. However, it’s clear that the idea that we can directly “observe” gender in this way assumes both cisnormativity and gender normativity: it ignores the fact that gender identity and gender expression do not always neatly align.

Likewise ignoring this fact, despite its close focus on trans existence, the Sullivan Report recommends that “observational coding” be used when collecting data. For example, Chapter 7 of this report is entirely dedicated to the notion that “the meaning of sex has become progressively destabilised” and nostalgically harks back to the practices of the pre-1990s era, with their “well-established understanding” which did not question the accuracy of “gendering”.

In Recommendation 20 of the report, Sullivan states that asking for a person’s sex/gender can be perceived as “rude” and suggests that the use of “observation” can avoid “potential dissonance and break of rapport”.

This ignores that failing to ask may equally well lead to misgendering, which itself is not simply “rude” but potentially deeply offensive, the source of inappropriate outcomes, and the stuff of harassment – besides being a potential source of data inaccuracy. Sullivan is here putting forward a disingenuous recommendation that is outright hostile not only to trans existence, but to anyone that does not align with gender norms.

However, Sullivan is not alone; “observational coding” is still commonly accepted as a practice in face-to-face surveys. For example, Eurostat, the organization that drives harmonization in statistical methodology across Europe, provides guidance on the collection of statistics states that “it might not usually be necessary” to ask what the correct value for “sex” is.

Where “administrative sources” are not available, such guidance is assuming that the “sex” of a person must be directly observable. Even recent reviews of survey practice that display some caution about “observational coding” fail to consider that gender norms cannot be simply assumed to apply across any segment of the population. For example, Cartwright and Nancarrow (2022) say, without evidence, that the validity of the practice is liable to be high, if one just neglects the existence of non-binary people:

Besides incorrectly assuming there must be a specific non-binary androgynous “look”, this also takes it for granted that the rate of misgendering cannot be significant in relation to the majority cisgender population.

Clearly, the practice of “gendering” individuals at a glance is so embedded in everyday life that the idea that it is can be wrong is very rarely considered by authorities. As we will see, the ESS data shows that this assumption is simply incorrect: the inaccuracy of “observational coding” is a significant, pervasive problem.

Types Of Gender Values In The ESS

The ESS is a large scale multi-national survey that aims to give a comparative view of social attitudes across European nations, by using a standardised set of question items that can be translated for use in different countries. It was established in 2001, has been run every two years since, and is a key part of European research infrastructure, with ERIC status.

Each round of the survey includes a standard set of questions divided into modules, reused in each round, plus a number of “rotating” modules, which are sets of questions that are specific to current research topics of interest.

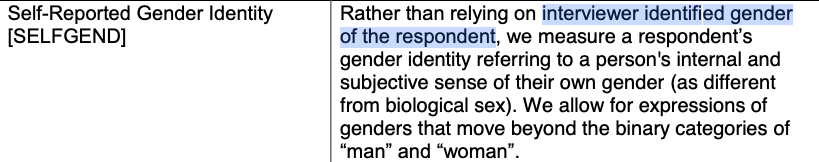

Round 11 of the ESS, run in 2023 across 31 countries, included a rotating module titled “Gender in contemporary Europe”. This introduced for the first time questions relating to gender identity, including item E1, intended to capture self-reported gender identity (SRGI) as opposed to interviewer identified gender (IIG), and to allow for non-binary gender to be recorded.

IIG has been recorded by the ESS in every round. In round 11 it is item F2 within the module on “Gender, Year of birth, and Household grid”, which can be given only binary gender values (“male” or “female”). Unlike other survey items, there is no specific ESS question associated with item F2 that is posed to the survey respondent. In fact, there are no specific, detailed instructions for interviewers in respect to this variable: the interviewer is simply told to CODE SEX.

There is no further elaboration on this instruction; it is assumed to be self-explanatory. Interviewers are expected to be able to simply and accurately perceive the gender of a respondent directly.

The use of two different measures of gender in the ESS gives us a unique opportunity to check how well IIG and SRGI align. As we will see, the IIG data recorded for some countries is far out of line from what we would expect, strongly suggesting that the practices used to “CODE SEX” are unreliable.

Gender Data Discrepancies In The ESS

All of the ESS round 11 data is freely available and the analysis tool allows for the relationships between different data items to be plotted.

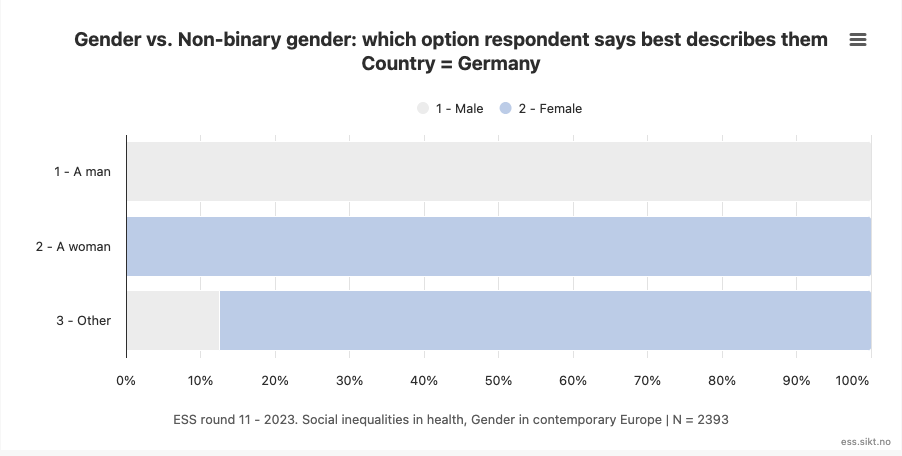

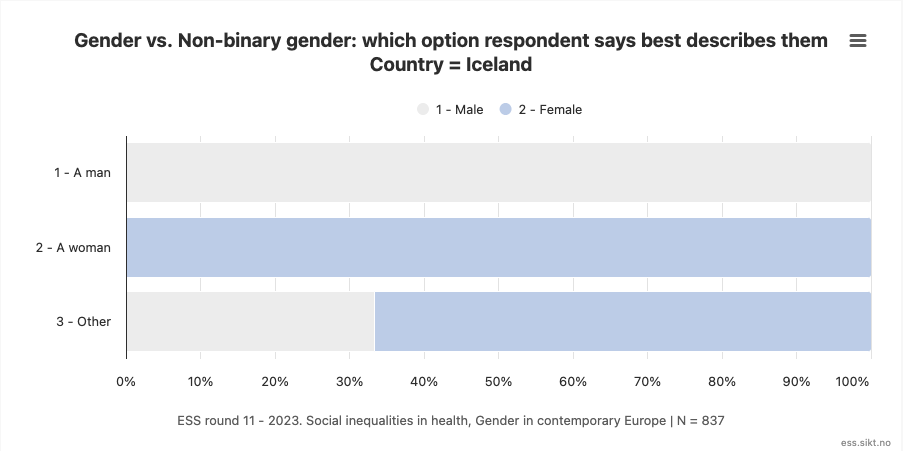

For some countries, we find that the two different measures of gender align neatly.

For example, both Germany and Iceland show 100% alignment between self-description as “a man” and “male” IIG coding, and likewise for self-description as “a woman” and “female” IIG coding.

(We will consider self-description as “other” later).

These examples of 100% agreement between SRGI and IIG (for “man” and “woman” categories) is likely to be the result of the interviewers in those countries following the instruction to “CODE SEX” by checking participant self-report about binary gender for item F2, just as self-report is used for item E1. This seems to be the only way to explain the perfect levels of alignment, given that other countries show serious discrepancies between the two measures.

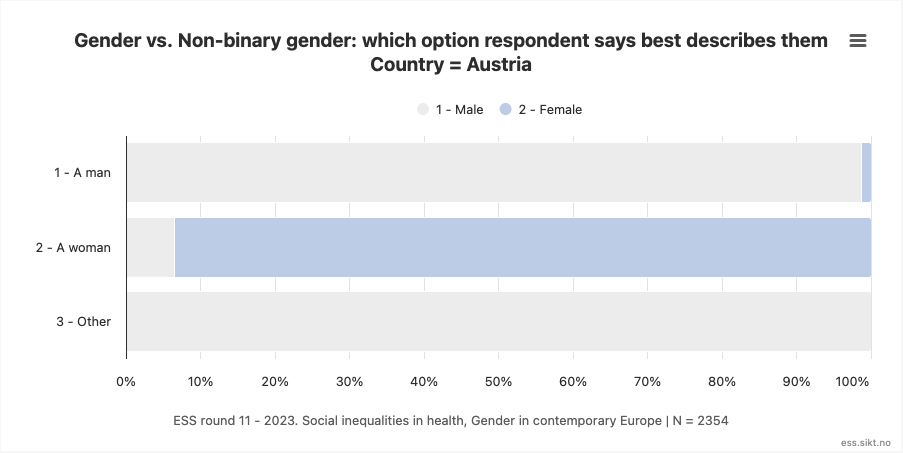

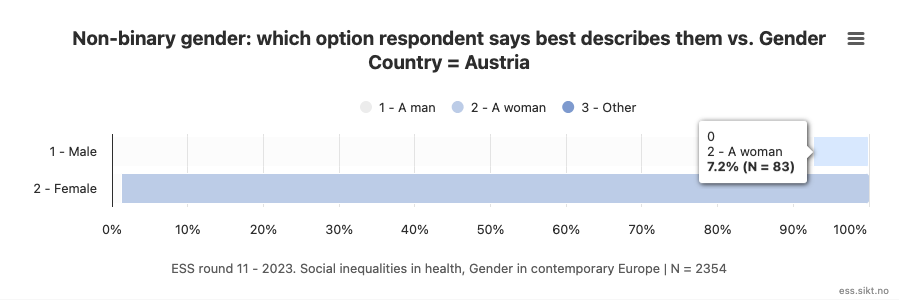

The most extreme example of disagreement is provided by the data for Austria, in which fully 6.5% of those whose self-described gender is “a woman” were coded with an IIG of “male”. Similarly, 1.3% as those who self-describe as “a man” were coded with an IIG of “female”.

This equates to 7.2% of the “male” coding by interviewers being misaligned with self-reported gender identity, and likewise for 1.2% of the “female” coding.

Many other countries show a similar pattern, with the discordance between IIG and SRGI particularly notable with respect to “male” coding. Examples of this pattern include Slovakia (4.2%), Ireland (2.6%), Cyprus (2%), Hungary (2%), the UK (1.8%), Greece (1.5%), and others to a lesser degree. (Inaccurate coding of men as “female” also occurs, but at much lower rates).

The fact that there appears to be systematic misgendering in play in these cases cannot be explained by reference to a set of transgender or non-binary (TNB) people perceived as not “passing”. While at first glance the mismatched IIG percentage levels seem to mostly fall within the range of estimates for the percentage of the population who are TNB (roughly between 0.5% and 3%), those size estimates are for the TNB population in its entirety. The very existence of the concept of “passing” tells us that only a proportion of TNB people might be coded with an IIG that does not match SRGI.

Some of the observed discrepancies are several times larger than could be accounted for even if every TNB person in the sample was misgendered (assuming TNB percentages in the sample mirror those in the population itself). The mismatch therefore must primarily represent the miscoding of gender for a portion of the cisgender population. Naturally so: because the cisgender group is roughly a hundredfold larger than the TNB population, even very low rates of gender misattribution applied to cis people will vastly overshadow any influence on data from the misgendering of TNB people.

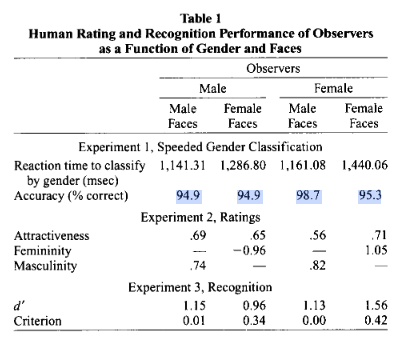

The single-percentage rates of gender misattribution for cisgender people this implies are not unreasonable; in fact we can see similar rates in other situations that allow for measurement. A laboratory study of gender classification by O’Toole et al (1998), for example, found a gender attribution accuracy of approximately 95% in a face classification task (slightly higher for female observers classifying male faces). The study noted that there was “no indication of a speed-accuracy tradeoff.”

This study was based on gender classification using photographs of young white adults only, so it does not account for effects of race or age on gender perception; nor does it tell us about the possible influence of additional gender cues available in face-to-face interviews. But it does clearly indicate that a rate of misgendering of several percent is not an unusual consideration, even in a situation where the targets were selected as representatives of a clearcut gender binary.

There are no obvious factors in the country documentation for ESS round 11 that might systematically explain the rate differences between countries, but naturally this raises a suspicion that different coding practices may have been followed in different countries.

Eurostat guidance states that “The quality reporting related to the variable 'sex' should contain information on the number of records where the sex is imputed”. We don’t have that information in relation to the ESS, but it is possible that different rates of gender mismatching across countries simply reflect the degree to which interviewers felt it acceptable to check with participants in cases where they were uncertain what to record as “observed”.

In any case, it is clear that the systematic direction in which gender is misattributed in the ESS is not random: there is a general cross-country interviewer tendency towards attributing “male” gender to people who identify as women, to a much greater extent than the reverse. This is showing a “male as norm” cognitive bias which is likely to have affected ESS data in every round.

As the “rotating” modules will change for future rounds of the ESS, cross-checking on IIG coding with SRGI as done here will not be possible in the future. However, the ESS is moving away from face-to-face interviews to a self-completion questionnaire model: half the data in Round 12 will be collected via self-report, and all of the data in Round 13. Presumably, then, “observational” coding bias in the ESS will shortly be no more: but it will have affected historical data, and such coding will continue to problematically be used and recommended elsewhere.

Implications Of Coding Bias

The discordance in the ESS results for gender shows that misgendering by interviewers is a substantial phenomenon, and this raises urgent questions about the extent of inaccuracies in any survey that has allowed this practice.

The erroneous assumption that cisgender people are highly unlikely to be misgendered has allowed a possible extensive, systematic bias towards “male” in gender attribution to pass unremarked.

A stated aim of the Sullivan Review was to ensure accurate data collection:

However, the report is repeatedly wrong in the assumptions it makes about what “accurate” information is, to the point where certain of its recommendations have potentially dangerous or fatal consequences – the inevitable outcome of forcing the systematic misgendering of the trans population in a medical context.

The ESS data shows another of those badly mistaken assumptions. Sullivan’s drive to return to “observational coding” has the potential to deliver massive inaccuracies in data of all kinds. Miscoding several percent of the population could reduce, eliminate, or even reverse evidence about gender differences within a population. The existence of systematic bias in interviewer coding of gender casts doubt on the accuracy of any statistics that have been gathered in this way.

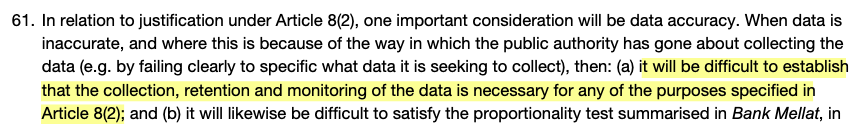

In this context it is worth noting that Appendix 1 of the Sullivan Report, a legal opinion, emphasises the importance of ensuring that data collected by public authorities is accurate. It states that data inaccuracies introduced due to the way in which data is collected will mean it is difficult to legally justify that the collection and retention of that data is compliant with human rights law.

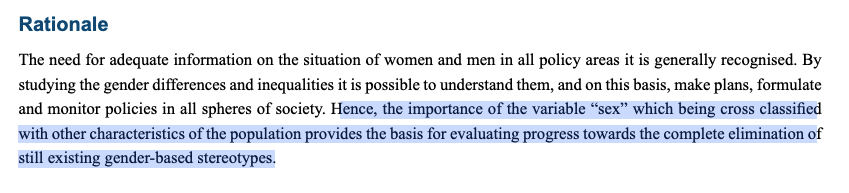

Eurostat states that “there are no technical issues” relating to “sex” as a core survey variable, and its rationale for using it says that the variable provides a solid basis for evaluating “elimination of still existing gender-based stereotypes”. However, this idea is very much undermined by the finding that interviewer coding of “sex” is biased under the influence of those self-same stereotypes.

The ESS mismatch between gender data items shows that Eurostat, Sullivan, and many others are simply incorrect on this: the assumption that “we can always tell” what the sex assigned at birth of a person is a nonsense; not just in reference to trans people, but in reference to the entire population.

Continued reliance on this practice is unjustifiable.

Non-Binary Gender Data In The ESS

The binary classification of “observation coding” does not align with the increased recognition of gender/sex states beyond the binary in recent years: legal status of self-identified non-binary gender in a number of European countries (such as Iceland, Germany and Malta); a parallel movement towards equal rights for intersex persons; and a broader scientific understanding.

The adoption of the “Gender in contemporary Europe” module in ESS round 11 in part reflects this shift, but the data relating to it raises important questions about survey design.

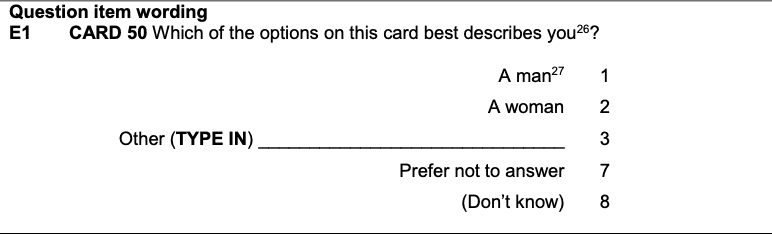

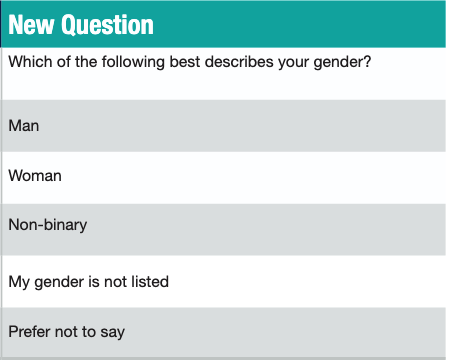

The module included a non-binary gender question (E1), pictured below:

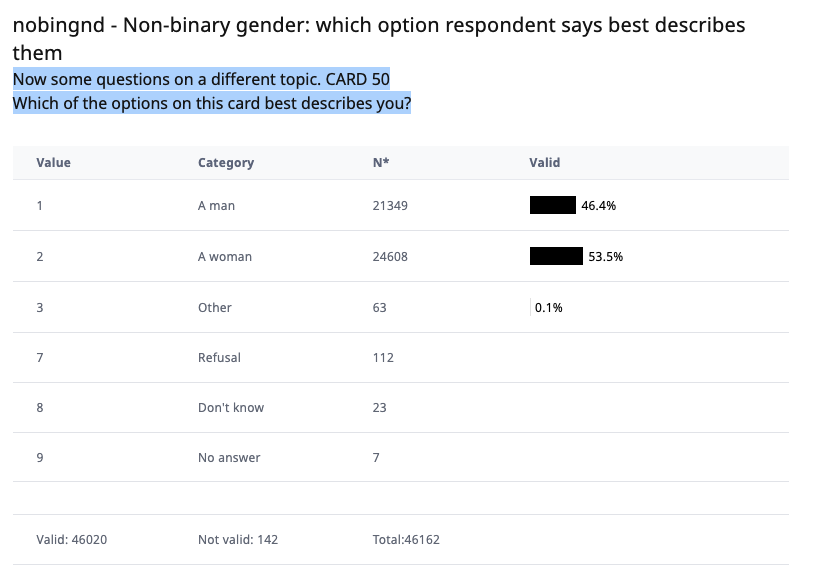

Only 0.1% of respondents to this question chose “Other” (N=63), an extremely low figure; approximately twice as many people refused to answer the question (N=122).

This is far adrift from the results of a 2021 cross-national survey by Ipsos which found across 27 countries that >1% of respondents described their gender identity in a way “other than male or female”. Specific countries in the Ipsos survey displayed notably higher rates (e.g. Germany was at 3%) and there was also a large generational difference (e.g. Gen Z was at 4%).

One possible reason for this discrepancy is that nowhere is there any context within the ESS module that makes it clear that question E1 is specifically about gender identity.

As the results table below indicates, the module is introduced to respondents only with the phrase “Now some questions on a different topic”. Following this, the question itself is simply “Which of the options on this card best describes you?”. That is an unclear opening to the module, which doesn’t clarify the context or purpose of this question.

The lack of context is deliberate: the ESS Interviewer Briefing documentation used by national co-ordinators explicitly states for item E1 that interviewers “should not provide any clarification at this question beyond what is on the screen.”

The question thus literally does not ask for gender as personal identity: it asks for an option that “best describes” the respondent. This does not account for the fact that TNB people repeatedly have to try and guess what exactly the intent behind questions concerning gender/sex is, in order to be able to give an answer that works for that context. Personal safety concerns may also play into whether a person wants to give an answer to a such a question that outs them as LGBTQ+ or not.

Coming in the middle of an extensive, formal survey, participants won’t naturally assume that self-identity is the target of the question as opposed to legal or medical status. Notably, of the countries surveyed, only Iceland had at that time introduced legal recognition for a self-determined third gender, and this county had the highest percentage of respondents that chose “Other”, at 1.1%.

The design of the module states that it is a response to the challenge that “we have been blind to a crucial societal development of anti-genderism”. However, the low numbers for “Other” gender means that it is unclear if the results are genuinely interrogating modern conceptions of gender.

Besides self-reported gender, the “non-binary gender” module also asks a number of questions about self-conception in terms of masculinity and femininity. The stated intent of this is to provide a more nuanced view of “gender identity”; the approach is based on the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI), a personality instrument that dates back to 1974.

It’s questionable whether working with a 50 year old instrument truly meets the aim of providing “new and innovative ways of measuring gender identity and gender salience”, particularly given that the BSRI gender model is strangely distant from modern, queer-informed conceptions of identity. The four personality types the BSRI identifies (masculine, feminine, androgynous, undifferentiated) do not fit with the idea that being non-binary does not equate to being androgynous, nor with ideas of gender fluidity that take “masculinity” and “femininity” to be transient aspects of self rather than fixed aspects of personality.

Conclusion

The data from ESS round 11 prompts the fundamental question: when we are measuring “gender” or “sex”, what is it we are actually measuring?

Assumed cisnormativity and gender normativity blinds researchers to the fact that it is methodologically absurd to work on the basis that interviewers can accurately “observe” something like gender that does not have a fixed pattern of manifestation.

We know that gender expression is historically and contemporarily volatile, and that societal association of notionally “gendered” traits with gender/sex classes have changed over time, yet survey designs still accommodate this assumption that “gendering” by observers is intrinsically reliable. The result can be, as we have seen, a strong androcentric bias in the data: several percent of the population who describe themselves as women may be coded as “male” by interviewers.

This should clearly not be how gender is recorded. It does not capture reality; indeed the reality is that gender/sex itself is not stable. Guidance and designs from the early years of the 21st century or before no longer reflect contemporary society, and the practice of “observer coding” is frankly an archaism.

The key challenge for the future is therefore to ensure that surveys use question designs that allow for contemporary gender data to be captured effectively, using an inclusive approach of co-design with gender minority groups, together with extensive piloting.

An example is this development approach from Ipsos, which reports that “people who are transgender or non-binary told us they find poorly worded gender questions exclusionary and difficult to answer from both an emotional and a cognitive point of view.” The answer that Ipsos reached was simple and elegant: it solicits information from participants by asking directly about gender, by using contemporary categories.

This starkly contrasts with the recommended approaches of the Sullivan Report, which far from engaging in co-design with minority groups, is clearly a transphobic document aimed at denying the existence of gender minorities within data and, more broadly, within society.