The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), the body responsible for promoting and enforcing equality law in the UK, has launched a consultation on changes to its Code of practice for services, public functions and associations, as part of the consultation, a draft version of the code has been published. On reviewing the draft code and comparing to the version currently in force, published in 2011, Trans Safety Network have noticed some concerning changes that may indicate shifts in the EHRC’s priorities. Among the changes, we note that:

- The draft code provides much fewer examples of unlawful discrimination against trans people. The current version of the code provides seven examples of unlawful gender reassignment discrimination by our count, all but one of these examples has been removed or changed to refer to other protected characteristics in the draft code, with only one new example added. This includes removing examples of discrimination by association and perception against cis women who support trans rights and cis women who are misidentified as trans.

- In the draft code’s section on exceptions for single-sex spaces, emphasis has shifted from protecting the rights and dignity of trans people to “balancing” trans people’s rights to equal access to public services and spaces against imagined conflicts of rights. Language that upholds trans people’s legal rights has been removed from the chapter at various points.

- While we welcome the draft code’s recognition that at least some nonbinary trans people have the protected characteristic of gender reassignment, the draft code strongly implies that some do not and shows a worrying lack of clarity on when this is the case.

- In the section of the draft code on religion and belief undue weight has been lent to the protection of “gender critical” beliefs with no detail on other political and philosophical beliefs that constitute a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010.

As documented extensively in past TSN reporting, the EHRC has been the subject of a great deal of concern in recent years with respect to its relationship to anti-trans organisations, interventions in policy debate about gender recognition law and increasing bias against trans rights. In this context, it is our view that the proposed changes to the code of practice reflect institutional transphobia and a lack of interest in enforcing trans people’s legal rights.

What is the Code of Practice?

Under the Equality Act there are 9 protected characteristics, 8 of which are covered by the Code of practice for services, public functions and associations (age, disability, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation), the act protects people from discrimination or harassment because of these characteristics. Trans people have the protected characteristic of gender reassignment, which refers to any person who “is proposing to undergo, is undergoing or has undergone a process (or part of a process) for the purpose of reassigning the person's sex.” For the purposes of the Equality Act, gender reassignment need not necessarily involve any medical procedure and includes non-medical forms of transition such as changes of pronouns, name or presentation. This means that it is unlawful for providers of services and public functions to discriminate against trans people, for example by refusing to serve trans people or providing us with a poorer quality of service because we are trans.

The Code of practice for services, public functions and associations is a document published by the Equality and Human Rights Commission that gives guidance to organisations providing services, public functions and associations on their obligations under the Equality Act. The code provides definitions of the various protected characteristics, who has those characteristics, what constitutes discrimination and harassment under the act (including some exceptions where discrimination is lawful) and how the act will be enforced. Because the EHRC is the statutory body which is responsible for enforcement of the Equality Act, this code of practice indicates the body’s priorities in terms of enforcement and can be used as evidence in court, although it is not in itself an “authoritative statement of the law.”

Changes to examples

Both versions of the code of practice feature examples to illustrate how the code should be applied. While these examples are not the letter of the code, they provide organisations with context for how to apply the code and reflect what the EHRC recognises as lawful or unlawful in its role as promoter and enforcer of equality law.

Several examples in relation to gender reassignment discrimination from the current code of practice either do not appear in the new draft code, have been altered to refer to other protected characteristics or have otherwise been significantly changed. While these changes do not mean that gender reassignment discrimination as described would be lawful or within the letter of the code, the removals suggest that the EHRC sees gender reassignment discrimination as less of a priority than it did in 2011 and leaves organisations using the code to shape policy and procedures with fewer examples to prompt them towards respecting and upholding trans people’s legal rights. What follows is not an exhaustive list of all problematic changes with examples in the draft code, but a series of illustrations of the issues.

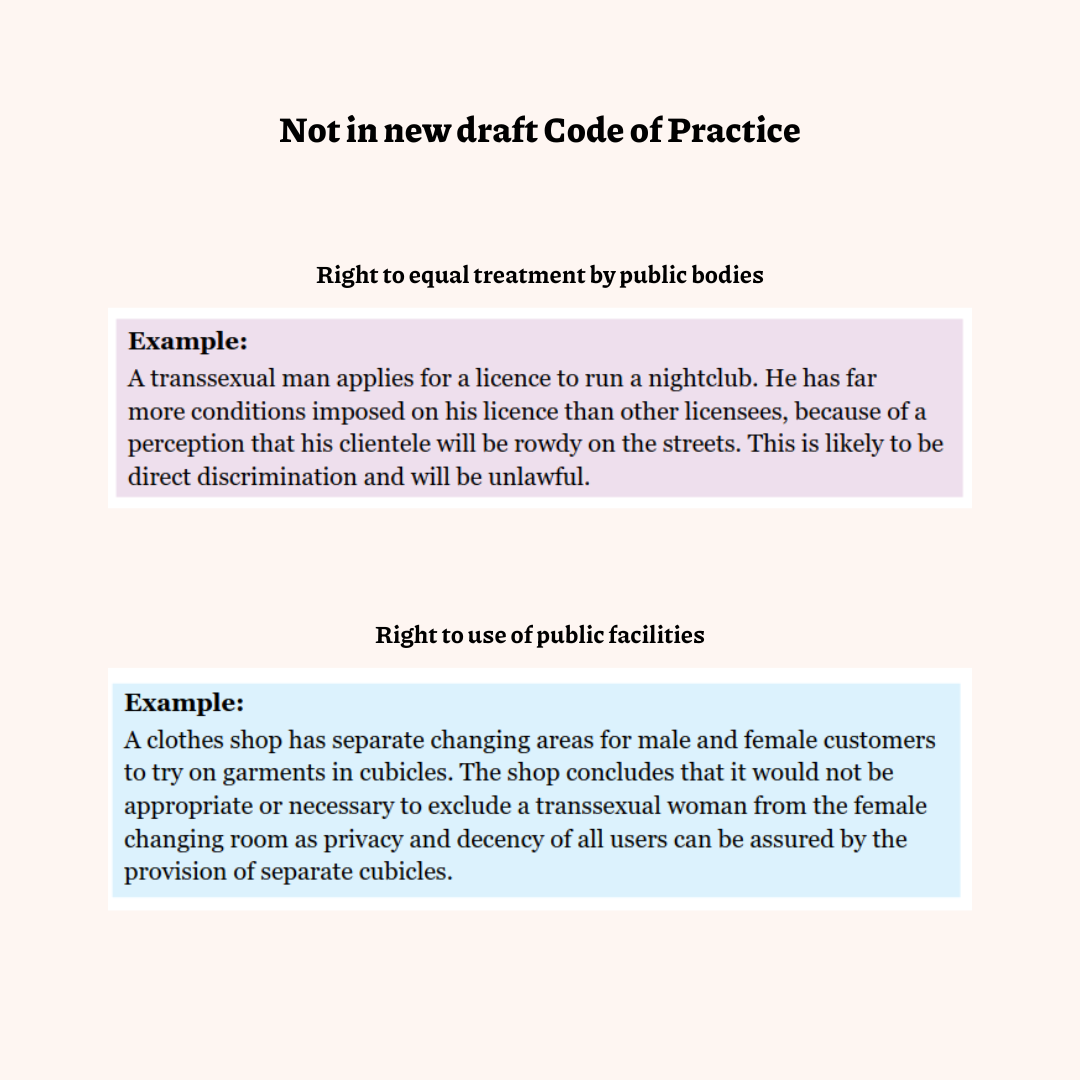

Some of the removed examples refer to crucial matters such as the right to equal treatment by public bodies (in chapter 11) and trans people’s use of public facilities (in chapter 13). We would urge the EHRC to restore these examples because they constitute clear guidance to organisations about our legal rights, which we note remain unchanged on these matters.

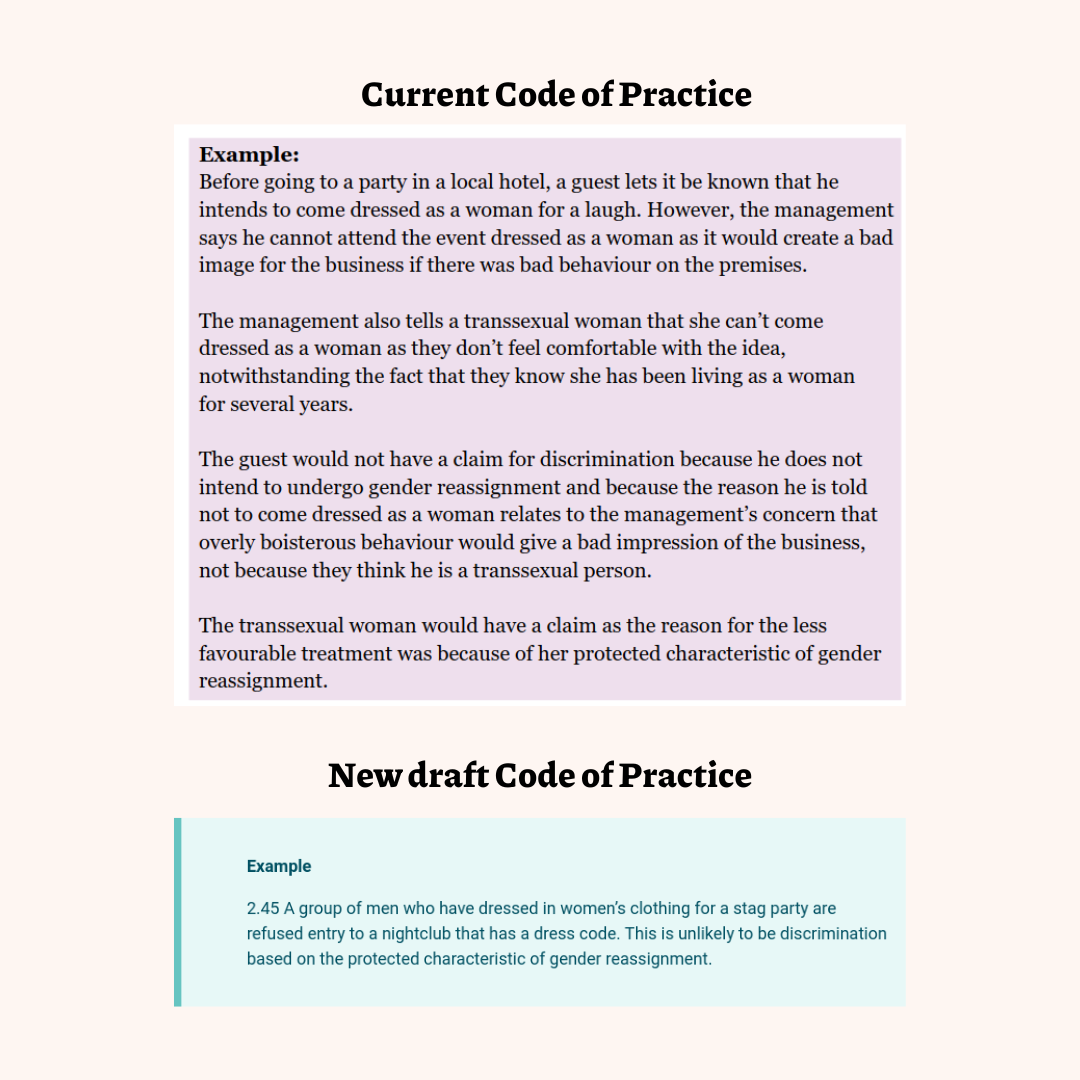

In a section of chapter 2 of the code of practice explaining the status of “cross dressing” (wearing clothing stereotypically associated with another gender) with respect to gender reassignment, the example given has been significant pared down in the new draft. Where the current example given clarifies both where “cross dressing” is protected by the law and where it isn’t, the new draft code only gives a clear example of were it is not legally protected. This is insufficient for giving organisations the full context of the law. Beyond the legal issues, TSN would also argue that no organisation should seek to police the gender presentation of people using their services and it is more important to highlight to organisations the legal risks of committing unlawful gender reassignment discrimination than to functionally give permission to police gender presentation in certain circumstances.

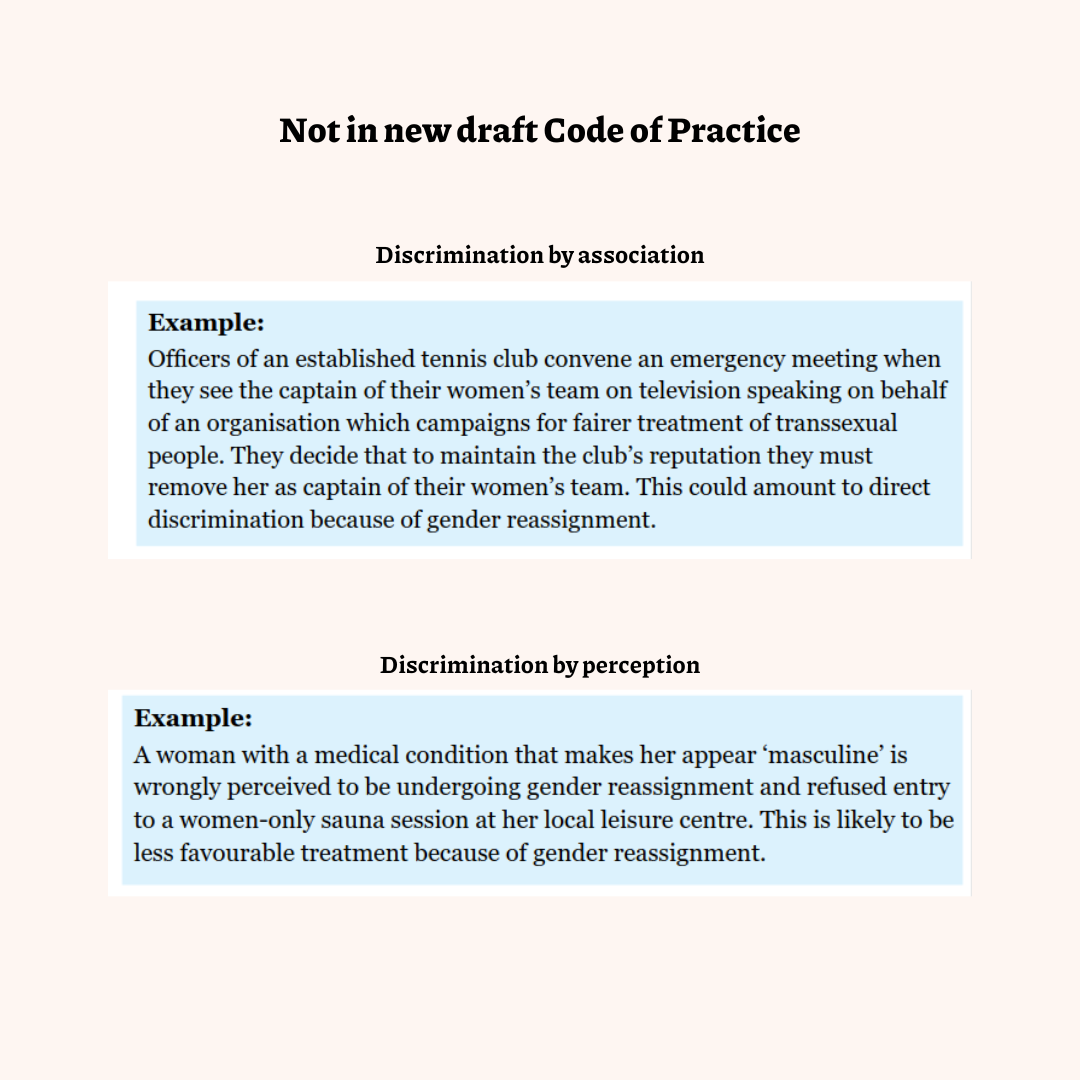

In the sections of chapter 4 of the code of practice explaining discrimination by association (where a person is discriminated against because they are associated with a person or people with a protected characteristic) and by perception (where a person is discriminated against because they are misidentified as having a protected characteristic), examples that relate to gender reassignment have been completely excised in the new draft code. The removed examples refer to a cis woman ally being discriminated against by a tennis club for supporting trans people and a cis woman “with a medical condition that makes her appear ‘masculine’” being discriminated against because she was perceived as trans. This is of considerable concern given recent, high profile examples of extreme harassment of cis women who vocally support trans people, the harassment of cis women in sports who have been misidentified by some as trans women both at professional and amateur levels and the large number of recent examples of cis women being misidentifed as trans due to gender nonconformity or medical conditions and harassed while using women’s public toilets. In the current atmosphere of increased anti-trans hostility cis women who are associated with trans communities by speaking out for us or who may be misidentified as trans women are at real risk of experiencing unlawful discrimination, harassment and victimisation of exactly the sort described in the removed examples. TSN would further note that discrimination of this form may disproportionately affect LGB women, disabled women and intersex women and should be of interest to the EHRC because it exists in the intersection of a number of protected characteristics (gender reassignment, sex, sexual orientation and disability).

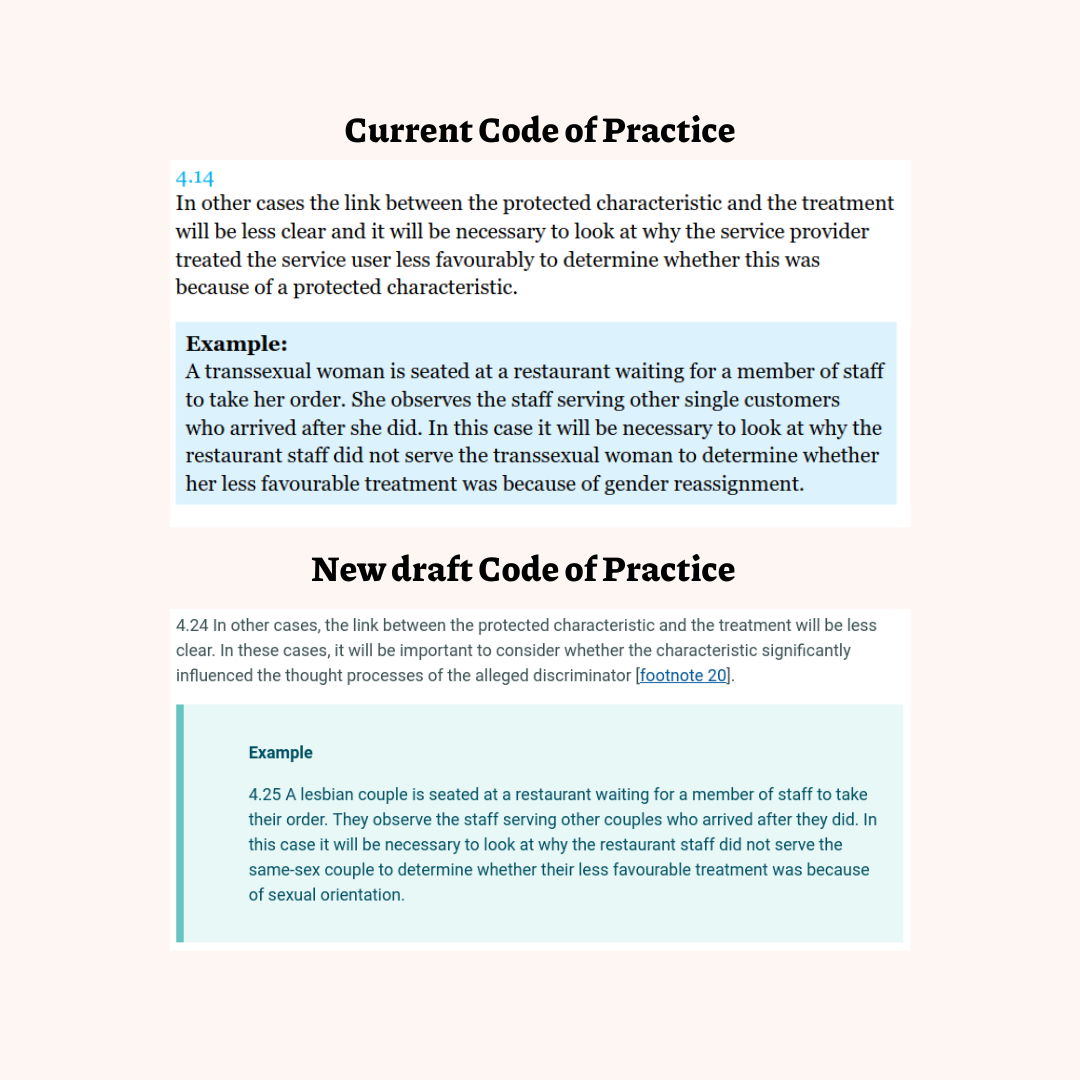

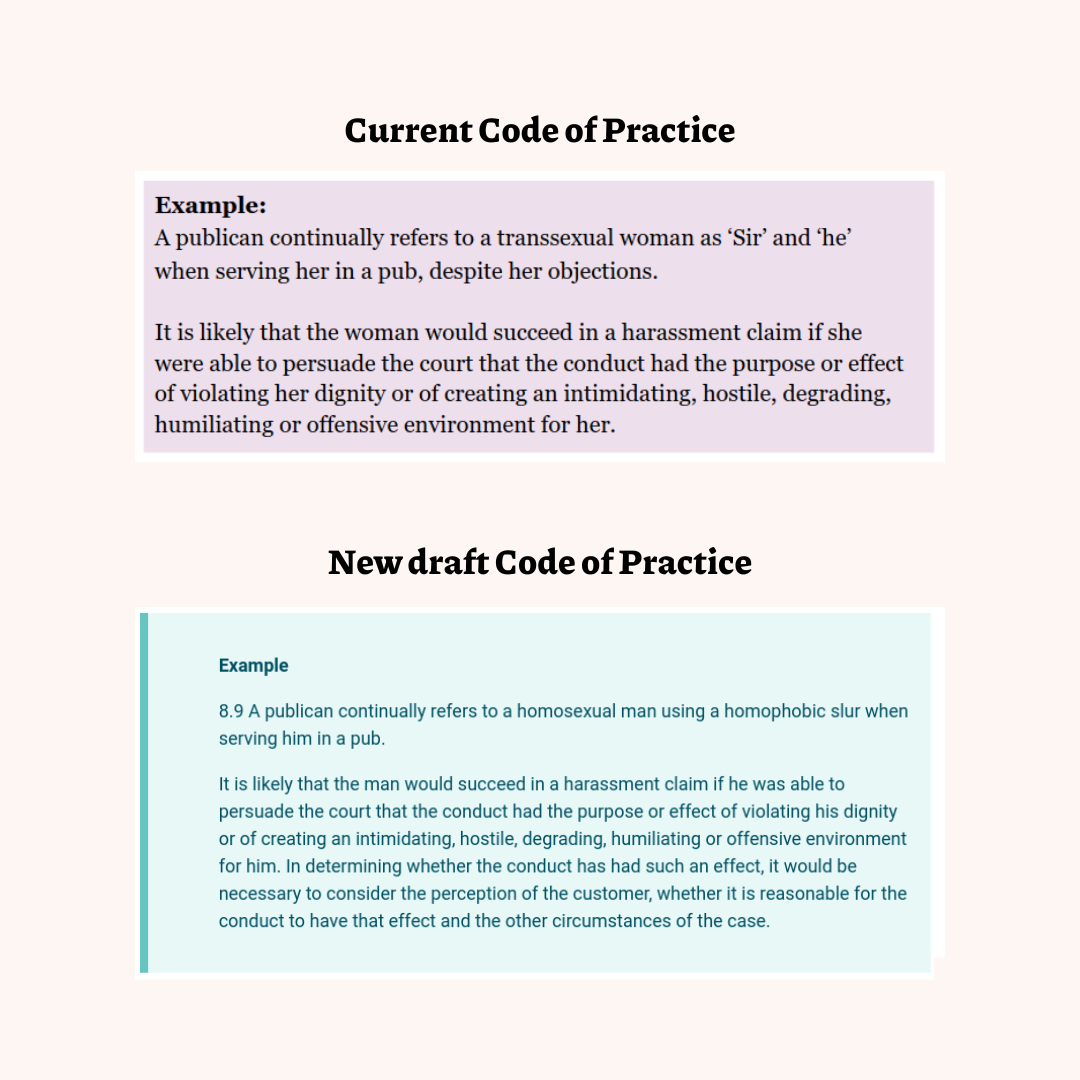

In one case, an example in chapter 4 of the code using the case of a trans woman treated less favourably in a restaurant has been changed to refer to a lesbian couple. In another, an example in chapter 8 of the code of when misgendering a trans woman can constitute harassment has been changed, also to refer to sexual orientation instead of gender reassignment. While TSN supports the legal right of LGB people to live free from harassment and discrimination, we are concerned by these changes in the context of the removals of other examples of unlawful anti-trans discrimination.

Exceptions for single-sex services and sports

The Equality Act contains a number of exceptions, situations where actions that would typically be unlawful under the act are allowable, these are discussed in chapter 13 of the code. The sections of this chapter of the new draft code on exceptions for single-sex services and sports have seen changes to the letter of the code and its emphasis.

The current version of the code of practice clearly and repeatedly emphasises the importance of trans people’s rights, safety and dignity, explicitly stating that when making decisions regarding trans people’s use of single sex spaces “The intention is to ensure that the transsexual person is treated in a way that best meets their needs” (paragraph 13.58) and that “the denial of a service to a transsexual person should only occur in exceptional circumstances” (paragraph 13.60). The current version of the code this section repeats the earlier call for exceptions to equality law to be applied “as restrictively as possible” (paragraph 13.60, repeating language from paragraph 13.2), the new draft code avoids reminding organisations of this when it comes to trans people’s rights, despite the earlier call for exceptions to be applied restrictively still appearing earlier in the chapter, now in paragraph 13.4.

Language upholding the rights of trans people has been largely removed from the new draft code, with a new emphasis placed on the basis on which trans people may be denied appropriate access to single-sex services. Where the current version of the code contains an example of a clothes shop lawfully deciding that changing rooms should be trans inclusive, the new draft version instead includes two examples, one of a dangerous and violent trans woman prisoner who must be housed in the male estate and one of a vulnerable elderly trans woman whose own right to single-sex care must apparently be balanced against the wishes of cis service users with no clear conclusion given. While in both versions the code is clear that trans people should be treated as the “gender in which they present” barring a strong justification for doing so, the new draft code seems heavily slanted away from the rights of trans people and towards providing organisations with justifications for blanket trans exclusion. TSN would reiterate that no part of the law with respect to single-sex spaces has in fact been changed.

In a concerning move, language stating that trans people may require use of medical services typically reserved for their assigned gender at birth, using the example of trans men’s access to cancer screening and gynecological services, has been removed altogether and neither version of the guidance discusses trans women’s access to breast cancer screening, despite comparable risk between the two groups. Trans people’s health needs with respect to “sex specific” healthcare are complex and the NHS’ failure to adequately account for these needs is a source of serious healthcare inequalities. TSN are concerned by the EHRC’s failure to address this in a code of practice that claims to clarify rights in service provision.

The section of chapter 13 that deals with gender reassignment and single-sex sports has seen similar changes. Where the current version of the code of practice states that exclusion of trans people from single-sex sports is lawful “if this is necessary in a particular case to secure fair competition or the safety of other competitors” (current code of practice, paragraph 13.45, emphasis added by TSN), the new draft code of practice states that such exclusion can be lawful “where an average person of one sex is at a disadvantage compared to an average person of the other sex” (new draft code of practice, paragraph 13.69). This change, moving the grounds for exclusion from a case by case basis to general exclusions based on averages derived from cisgender athletes, is a backwards step in the EHRC’s recognition of trans people’s right to participate in sports.

Lack of clarity on nonbinary and genderfluid people’s legal rights

In chapter 2 of the new draft code of practice, which provides definitions of the 8 protected characteristics under the Equality Act, paragraphs 2.42-2.43 provide some recognition of nonbinary and genderfluid trans people. This is not present in the current version of the code of practice. However the draft code caveats this protection of rights, saying that:

People with non-binary or gender fluid identities will only be protected if they meet the definition of gender reassignment as set out in the Act - EHRC, draft Code of practice for services, public functions and associations, chapter 2, paragraph 2.42

The draft code goes on to give the example of a person who is genderfluid in the sense that “they are transitioning from one sex to another and on some days they will present as female and on other days as male,” outlining an example of unlawful gender reassignment discrimination against such a person, this is the only new example of clear gender reassignment discrimination added to the draft code. The exact criteria necessary for a nonbinary or genderfluid person to meet the EHRC’s criteria is not made explicit and, with the example given, these paragraphs could be read as suggesting that genderfluid and nonbinary people who do not see their identity as an intermediate stage in a binary transition do not have the protected characteristic of gender reassignment. Such a reading would be at odds with the ruling in Taylor v Jaguar Land Rover, a case where a genderfluid trans person made a successful claim for discrimination on the basis that she was genderfluid, in which the tribunal found that the clear intent of the Equality Act was that nonbinary and fluid modes of transition were covered by the language of the act, stating:

it was very clear that Parliament intended gender reassignment to be a spectrum moving away from birth sex, and that a person could be at any point on that spectrum. That would be so, whether they described themselves as “non-binary” i.e. not at point A or point Z, “gender fluid” i.e. at different places between point A and point Z at different times, or “transitioning” i.e. moving from point A, but not necessarily ending at point Z, where A and Z are biological sex. - Employment Judge Hughes, Ms R Taylor v Jaguar Land Rover Ltd - Reasons, paragraph 178 [emphasis added by TSN]

While TSN welcomes the EHRC’s recognition that at least some nonbinary and genderfluid people have the protected characteristic of gender reassignment, the way in which this is phrased and the example given appear, in TSN’s opinion, to be at odds with case law. As it stands the draft code of practice fails in its stated aim to give clear guidance on the law and could mislead a service provider into believing it was entitled to discriminate against some nonbinary or genderfluid people.

Religion or belief

The section of chapter 2 of the code on the protected characteristic of religion or belief contains a subsection on manifestation of religion or belief. This subsection is largely unchanged from the current code of practice other than the addition of “expressing gender critical views online” to a list of examples of manifestation of religion or belief (paragraph 2.78).

The addition of the expression of gender critical views to the list is notable because it is the only reference to a set of political beliefs made in the list. In the context of other changes to the code that indicate a lack of interest in defending trans people’s legal rights the addition of expression of a set of beliefs regarded by some as a set of dogwhistles for transphobia but not, e.g. belief in climate change (at issue in the case that gave rise to the Grainger criteria often cited in legal cases relating to religion or belief), support for Scottish independence or ethical veganism, could be read as suggesting a particular ideological slant. We would further note that the expression of “gender critical views” is not absolutely protected and whether any specific case of gender critical views constitutes a protected characteristic will depend on whether the views being manifested meet the Grainger criteria.

Positive developments

Despite a number of serious concerns outlined above, TSN would like to note some positives about the draft guidance. Some of these are positive aspects of the current code of practice that are retained in the new draft version, while others are new, positive developments.

- The one example of unlawful gender reassignment discrimination retained from the current code of practice is one that clearly shows that employers have a duty to act to prevent their employees from discriminating against trans service users. In light of several recent high profile legal cases in which school employees have sought protection for discriminating against and mistreating trans students, this recognition of the duty of employers to protect trans people from discriminatory conduct is welcome.

- The new draft code of practice repeatedly emphasises that a trans person need not have a gender recognition certificate (GRC) to have the protected characteristic of gender reassignment (paragraph 2.47). The draft code also states that excluding trans people from single-sex services without good reason is unlawful “whether the person has a GRC or not” (paragraph 13.113).

- The segment of chapter 4 on discrimination because of pregnancy and maternity now includes an acknowledgement that trans men “could also experience pregnancy and maternity” (paragraph 4.54).

- Language protecting the rights of trans children and young people in chapter 2 of the code of practice has been strengthened. The new draft guidance plainly states that “There is no minimum age for the protected characteristic of gender reassignment” (paragraph 2.41). This clear statement that trans youth have a legal right to the protections of the Equality Act is vital in the context of both the Department for Education (in draft RHSE guidance) and the NHS (in response to a legal challenge from Good Law Project) recently having falsely claimed otherwise.

These positive aspects of the new draft code are useful and important. However TSN remain seriously concerned about the wider issues of the new draft code downplaying the legal rights of trans people. Human rights are not a “balancing act” but a legal tool that can be used to protect minority groups against hostile action by state actors and companies.

Editorial note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that there are 8 protected characteristics under the Equality Act 2010. There are 9 protected characteristics, one of which (marriage and civil partnership) is not covered by the code of practice discussed in this article.